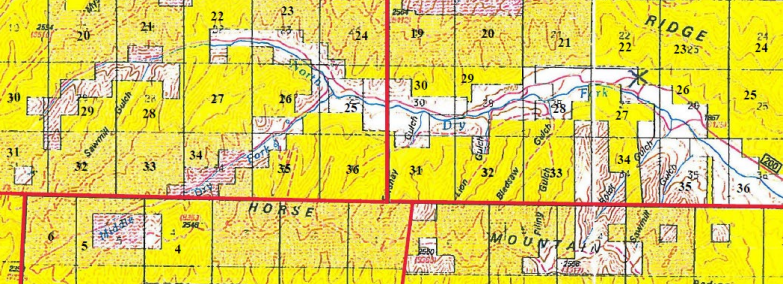

A portion of roadways subject to litigation between Garfield County and the High Lonesome Ranch west of De Beque has been deemed not to be a public right of way by a district court judge who reconsidered the matter following a 2023 appeals court ruling.

The ruling this fall by Senior U.S. District Court Judge R. Brooke Jackson applies to the portion of the North Dry Fork Road, also known as Garfield County Road 200, west of where it splits off from Middle Dry Fork Road.

County Road 200 east of that intersection heading toward De Beque remains public, as does Middle Dry Fork Road west of the intersection, consistent with Jackson’s ruling in 2020 in the case. But the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ordered Jackson to take another look at the portion of North Dry Fork Road west of the intersection.

The ranch used to have a locked gate barring public travel further west up North Dry Fork once the road reached its property. Following a trial, Jackson ruled in 2020 that North Dry Fork Road from the gate to the intersection with Middle Dry Fork Road, Middle Dry Fork Road and North Dry Fork Road west of the intersection all are public rights of way.

He found that based on state law, North Dry Fork Road up to its intersection with Middle Dry Fork, and Middle Dry Fork Road itself, long ago had become public based on their historical use for at least 20 consecutive years, and the fact that the county never acted to abandon the roads.

As for North Dry Fork Road west of the intersection, he found that it had become a public right of way under provisions of Revised Statute 2477, an 1866 federal law in effect until its repeal in 1976. The question was whether the road had been used enough to make it public before the road was removed from the public domain under patent claims. Jackson found that it was, based on a Colorado Supreme Court standard under which use of a route by even one person “for whom it was necessary or convenient” meant the road was public.

The appeals court found that standard out of step with its decision in a Utah ruling and sent the question back to Jackson for reconsideration. In his September ruling, he found that the evidence of historic use on the road west of the intersection in its early days “lacks the frequency, and certainly the variety and intensity, of use that the Tenth Circuit had in mind in defining a public highway.” Thus, he found, that portion of the road isn’t public.

Jackson also ordered that the roads that remain public based on his previous rulings are to be 32 feet wide. The county argued for a 40-foot width, and the ranch called for a 30-foot width on North Dry Fork Road east of the intersection and just 15 feet on Middle Dry Fork Road.

The ranch had argued that given the way the litigation turned out, it shouldn’t be obligated to pay the county’s costs at trial.

Jackson responded in an order Dec. 30, “In other words, (the ranch is arguing that) because the Tenth Circuit reversed and remanded a portion of this Court’s order, the Ranch is entitled to assume that the County was not the prevailing party and renege on its agreement to pay the County’s trial costs. Baloney! The County was and remains the prevailing party, and the costs are to be paid promptly.”

Those costs total just under $33,000.

Brandon Siegfried/Special to The Daily Sentinel

FILE PHOTO- A locked gate bars access on North Dry Fork Road, one of the roads west of De Beque that have been the subject of a legal dispute between High Lonesome Ranch and Garfield County.

Brandon Siegfried, a Mesa County public-land-access advocate who first asked Garfield County to seek to get the gate unlocked, said his focus had been on opening up the stretch of North Dry Fork Road connecting to Middle Dry Fork Road, and gaining access up Middle Dry Fork as well.

“We were just hoping to reconnect with that (Bureau of Land Management) land up Middle Dry Fork, basically,” he said.

He said the county decided based on its own research to also seek the opening up of the portion of North Dry Fork Road west of the intersection.

Despite the latest court ruling, the lawsuit still led to much-improved access to a large amount of BLM land that previously was much more difficult to reach.

“Fifty-some thousand acres open to the citizenry again, that’s a victory, and the citizens get to use their land, and that’s all that we were after” said John Martin, who recently finished up a long tenure as a Garfield County commissioner.

As a commissioner he was heavily involved in the effort to get public access restored to the roads.

Said Siegfried, “It’s beautiful country up there and it’s been opened up to the public. Overall I think it will be a good thing for public land recreation.”

Jackson noted in his September ruling that while the BLM has been a party in the case, “for the most part it has not actively participated in it.” But as he reconsidered the status of western portion of North Dry Fork Road, the BLM argued that the county hadn’t shown that the historic use of that road segment warrants right-of-way status under the Utah ruling standard applying to RS 2477 matters.

Previously, the county noted in a legal filing, the BLM hadn’t opposed the county’s request for a ruling that all the disputed road segments are public.

Contacted by the Sentinel, the BLM declined to comment on its change in position. Martin thinks the change was political, due to changing presidential administrations and BLM directors, and some new local BLM officials. The trial in the case occurred during the first Trump administration; the appeals process and Jackson’s reconsideration of the status of the one road segment occurred during the Biden administration.

Siegfried said he wasn’t surprised about the position the BLM took on the RS 2477 question. He said the BLM isn’t a fan of RS 2477, which he called “a pain in the back side for them.”

He said the agency ignores that law when choosing to close routes itself, and if counties disagree their only recourse is to take the BLM to court.